Featured Artist: Krista Franklin

interview with Asha Iman Veal, for Arts Alliance Illinois (July 2020)

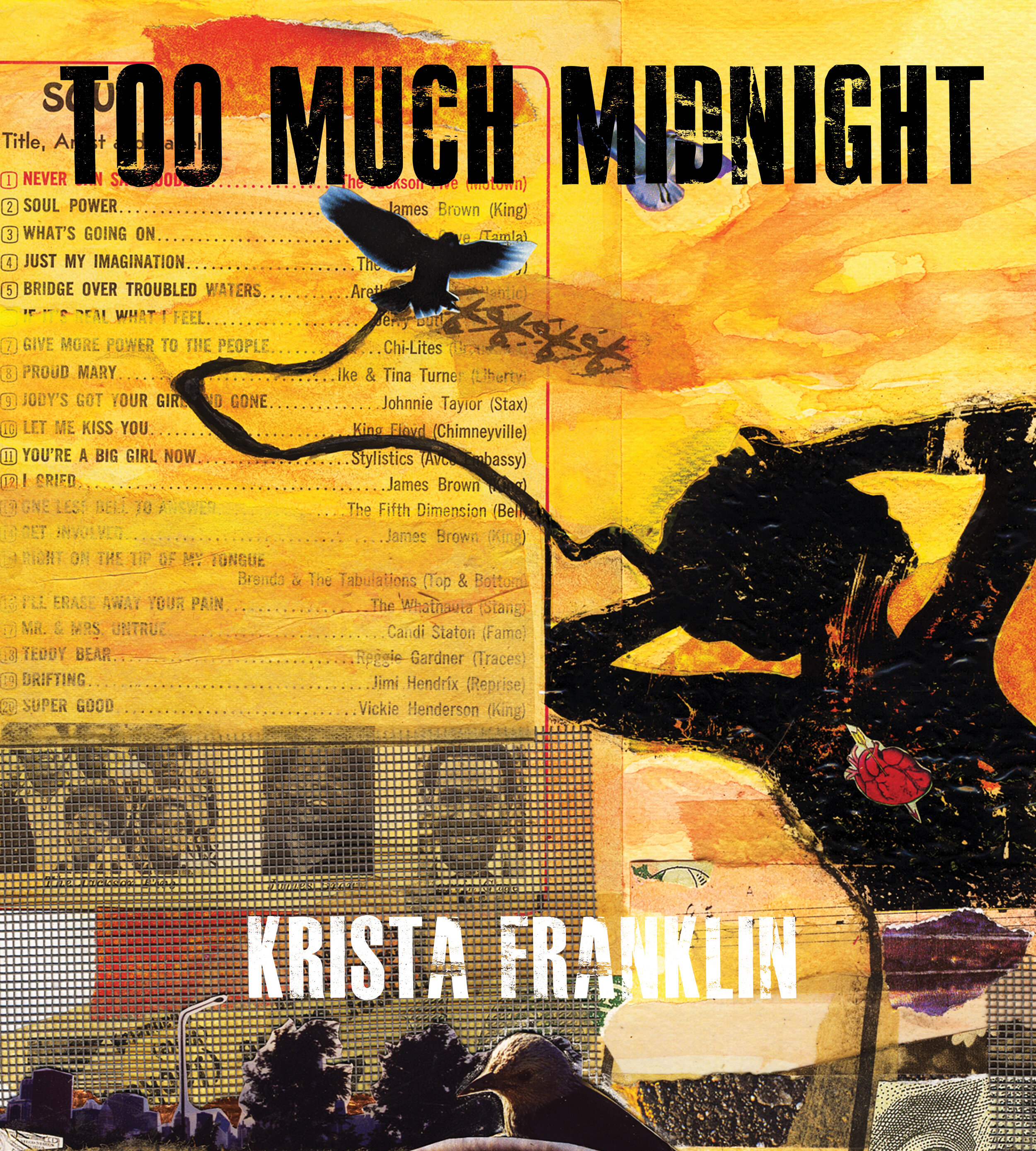

(Too Much Midnight by Krista Franklin, released 2020 by Haymarket Books.)

In 1983, writer Alice Walker asked the following: “What did it mean for a black woman to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? In our great-grandmothers’ day? It is a question with an answer cruel enough to stop the blood.”

Today, Too Much Midnight (Haymarket Books, April 2020) by artist and poet Krista Franklin is a book that generational knowledge has gestated, yearned for, and awaited. Franklin brings a gorgeous blend of visual and literary arts. She shares an elegant, exquisitely honed ability to recolor and create scenes of life.

Franklin’s poems and images reveal experiences, realities, and whole worlds that have not ever been affirmed by limited imagination or privilege binaries.

For the rebellion of 2020, this is the book of the year.

The following conversation took place in Summer 2020, between Krista Franklin and Asha Iman Veal.

Too Much Midnight by Krista Franklin is available in hardback as a release by Chicago’s Haymarket Books.

(“On the Blk Hand Side” by Krista Franklin, 2006)

Asha Iman Veal:

Without poets, it might be nearly impossible to connect with the truth that life is full of possibilities beyond what the status quo presents. It would definitely be a lot harder to see and understand ourselves. Several times while reading Too Much Midnight, I felt like this book held the thing that we all needed, and even had an unmet hunger for, while existing in whatever place, town, neighborhood, or nation that never fully felt like a loving home or fit. So, Krista, I am curious to ask you, What is this true magic of poets and poems?

Krista Franklin:

For me, poetry is the language of the heart and the mind. It operates on multiple levels, so there are things that can be said in poems that cannot be articulated in other forms. Poems can be constructed in a way that truly hits the emotional core of the thing. I feel like poetry does a kind of work that no other genre can do.

People are funny to me because as much as I hear folks talk about how they hate ‘feelings,’ every single decision that people make is based on them. Every single one. It’s so ridiculous to have these conversations where we decry or denigrate or talk about how we don’t want to have feelings. I’m like, ‘Really? Because everything you do is based on your feelings. Now you might not necessarily like it or want to talk about it, but that’s what it is.’

It’s interesting to think about poetry as one of the languages of the heart—but I also don’t want to promote the notion of poetry as a tool of sentimentality. A lot of people in the mainstream think, I write poems when I’m sad, I write poems when I’m happy. No, you write poems because you’re trying to work through an idea. You’re doing a deep work, a very deep and critical work. You are not just writing down your feelings like you do in your journal and then reading it in public.

A poem is an actual craft. It’s a construction. It requires a lot of attention, a lot of time, and a lot of vulnerability that most people really do not want to do or be. Poems have a very powerful role in our society, because they open gateways, portals, and doorways of understanding and hold the nuances of our experiences as well.

(“If You’re Still Burning, Keep Breathing” 2006)

Asha:

Something so magnificent in your writing and poems, Krista, is in the references that you bring. You bring whole lives, whole worlds, histories, and intimacies of culture. From the poem ‘Black Bullets’ specifically, I’m wondering about the lines: This is not a war of the flesh. But of the spirit(s). Could you share more about the meaning?

Krista:

‘Black Bullets’ is a poem about Black mothers. It’s a poem about Black women who have lost their children. It’s about loving someone so deeply—because your body is the literal site for the architecture of this person. To have formed a whole human being inside your body, a seed that grows—and then someone comes and snatches that away. The line in my poem, ‘this is not a war of the flesh, but of the spirits’ is a section of a scripture that I’m paraphrasing. I think a lot about scriptures, and that shows up in my writing. Another one that always haunted me, even as a child, went something like, ‘the devil comes as a roaring lion to steal, kill, and destroy.’ Roaming around causing havoc that no one can see. That shit used to terrify me. Still does kinda.

‘Black Bullets’ is my attempt to honor the women who have lost their most precious beautiful thing at the hands of a maniac, simply because of an idea, an idea that existed solely in that person’s head in that pivotal moment, completely imaginary. This poem also grapples with the notion of Ancestors and the spirit world being at war with forces that are not for our highest and greatest good. That’s something I was taught as a child growing up in the Pentecostal church. It always felt terrifying for me yet intriguing to think that there was another world that was happening right alongside our world that we couldn’t see. These ideas about Heaven and earth, and the implication of unseen forces at work.

Spiritual work and spiritual war. There are several Biblical stories that revolve around war—that’s probably something in every holy text that's ever existed from the Bible to the Qur'an.

(“Drapetomania #2” 2006)

Asha:

Throughout Too Much Midnight many of the poems identify and explore spaces of violence—ways that violence can take away loved ones and families, as well as how histories of persecution remain visible on the bodies of survivors. From the poem ‘It’s the Skin that Tells’ will you tell us more about this story, and your neighbor’s coat?

Krista:

‘It’s the Skin that Tells’ details the emergence of my awareness around genocides and the genocidal nature of humans. When I was a kid I had the pleasure of meeting a man named Otto, may he rest in peace, who was a beautiful man who lived next door to my aunt and uncle in Cleveland. My aunt and Otto would stand at the fence that separated their properties and just talk to each other. I was probably around 13, 14, maybe younger. My aunt and Otto would have these long conversations—a Jewish elder and my young Black aunt—and she’d bring him food, he’d bring her food, and they just stayed chatting.

He was very tender, very sweet, very calm. He’d lost his family in the Holocaust. Terrible things happened to him, yet there he was, across this fence, just being as sweet as he could be. Not wanting to hurt anybody. He was like an angel to me.

One day he was standing at the fence with a coat in his arms; it was the coat that he wore when he left Germany. He said he didn’t want it anymore, he didn’t want to carry it, and he wanted to know if I wanted it. It always stuck with me, what that coat symbolized for him. Also, he had the tattoo of the numbers on his arm. So mostly this poem is an honor and homage to Otto, but it’s also me grappling with the idea of evil. Encountering people who have survived evil, and even spaces that I’ve been in where I was able to evade evil even though it was staring me right in my face.

(“World Peace at Your Fingertips” 2008)

Asha:

I feel especially curious to hear more about a pair of lines from your poem ‘Quick Calculation’: ‘My mother warns, you make it look so easy. Each morning I wake on sweat-soaked sheets.’ That description makes me think about how as Black women we apparently make so many things in our lives look easy—even though none of this has ever been easy. So how do we make things better, in a way of being able to truly meet our needs?

Krista:

I’ve been thinking a lot about my mother in the 70s and 80s—just so gorgeous. She always talks about how one of our gifts (and curses) is that we make hard work look real easy. We were taught to make it look easy. We saw our mothers do it. We saw the women around us do it. They were juggling twenty-five-thousand things yet they still moisturized and looked fly. It’s Black Magic. That's what we do. But you are absolutely right with your comment before; we do not get what we need by being superwomen, by being like, ‘Look at me, I’m juggling the world and I still look phenomenal. I’m Clairol Girl No. 5.’ Meanwhile, our emotional lives are in shambles, our nervous systems are shot, and our hearts are broken.

I think it’s time for Black women in particular to fall back. Not in a sense of relinquishing anything, but in the sense that we have to start setting boundaries around our care. Nurturing ourselves and each other—because life is hard. We do double work because we navigate spaces that are anti-Black, anti-woman, and hostile as fuck. We navigate this sea and it’s constant. My prayer though is that soon, very soon, Black women are going to get the kind of care and nurturing, the love and the protection that we deserve and need. That is my prayer every day.

My prayer is for the healing of this nation, and for the healing of men. That our fathers and uncles and brothers and cousins and nephews be healed, that they recognize that they have been existing in and supporting a system that is not only undermining them but everything around them.

Asha:

In a way this feels like the dilemma that’s central in the poem ‘How Storm Rethinks Her Position’. I love how this poem explores the mind of an iconic Black woman within the very well-known fantasy universe of The X-Men comics. It’s easy to imagine how the best life would be possible as an X-Man—but Storm shows the complicated reality.

Krista:

I have a thing for the X-Men. I love the X-Men. There’s long been the analogy that the X-Men is a retelling of the Civil Rights Movement, but that’s not true. It’s unfounded, but I believed it for a long time too. If you look at the ideologies of what two of the primary characters, Xavier and Magneto, represent, it could be distilled into separatist ideology and integrationist ideology: King, Malcolm. That’s not where it came from, but it’s easy to make that analogy.

In ‘Storm Rethinks Her Position’ I’m thinking through the idea of Storm considering the benefit of a separatist stance. In Storm’s case she's like, ‘I can fly in the sky and cause an entire thunderstorm to end you, to end you with nature, to literally put your shit to rest co-creating with Mother Nature.’ To harness that kind of power, yet to still want peace... So I wanted this Black woman—who was one of a few Black characters in the X-Men lineage—to sit in her room at the end of the evening considering, ‘What am I doing here? Why am I fighting for human beings when they want me dead?’

You would think that Storm is free—she can fly, and we associate flight in our imaginations with freedom—but really she’s a superhuman trying to help humans be better humans, and that’s no fun. That’s not freedom.

(“Never Can Say Goodbye” 2010)

Asha:

Krista, there are so many references to songs and music in your poems and also in your visual work. Can you share a bit about what inspires this? Also, I sometimes think about poetry as a similar form and way of artistic magic as songwriting or musical composition, but maybe that’s not the case?

Krista:

There have been times that I’ve been on stage with musicians and had the pleasure of working with musicians. At the performance that Ben LaMar Gay and I did in Folayemi Wilson’s exhibition at Hyde Park Art Center, there were times when I would forget that I was performing and I would just be listening to him like I was in the audience, and then remember I was on stage with him. Music hits you in your heart space, and you become enraptured. It can envelop you and enrapture you in a way that no other form can do. Language can do it, but it takes a different kind of work, more work. Sonics transport us. Poems can do it too, but I think it requires a different kind of attention, a different kind of work.

I try not to envy anybody, but I envy musicians and I envy singers. I envy them because they have power over sound, they have power over notes. Notes do a different kind of work than language.

(Under the Knife by Krista Franklin, published 2018 by Candor Arts)

Asha:

On the topic of form, I am curious to ask what ‘memoir’ as a form and a genre means to you. I think about memoir as a style and tool, even when reading a work such as Too Much Midnight—a book of poetry. There’s also your book Under the Knife, a gorgeous project of artist’s book and memoir.

Krista:

In terms of memoir and poetry, I think what people see in my work has to do with the ‘confessional,’ what used to be called ‘confessional poetry’ based on personal stories. It’s been shunned in high art and poetry circles, to me, primarily because it’s seen as women’s craft, or seen as writing about yourself all the time. As if the ‘self’ is separate from ‘universal.’

I think memoir is different though, and potentially dangerous territory. The writer is telling a story that may or may not coincide with somebody else’s experience of the same events. Memoir can bring into question other people's intentions, movements, and life choices, as well as the authors’ own. I like memoir in the sense that it opens up spaces where we can see ourselves at our best and our worst. We can be very thoughtful as it offers an opportunity to look deeper into the human condition and why people do the things that they do.

People think that autobiographies and memoirs are the same thing. They’re not. Memoirs, to me, are more in the emotional landscape. They’re somewhat based on fact, sometimes. I like to think of memoir as a place to lay yourself bare; vulnerability, emotional transparency, and emotional sophistication. You have to know yourself well enough to be able to truly articulate the complexities of your own experiences.

Under the Knife, my book with Candor Arts in 2018, was my exploration and attempt in the realm of memoir. It’s the book that precedes Too Much Midnight. Under the Knife is an artist book where I took a lot of creative liberties, particularly with the idea of ‘genre’, and with the idea that memory is ‘truth.’ I don’t believe that memory is always truthful, which can be a radical and even dangerous idea to have.

(Krista Franklin, 2019)

Asha:

In a final inquiry, I’m curious to ask what it means for you as an artist to bring into the public such powerful depictions of Black women at the center of the narrative, in a space that’s sharing and collaborative—a space that’s not mediated by and not centered around anyone else.

Krista:

I suppose I hold some radical ideas, yet I definitely have to work against my own prejudices and belief systems and hopelessness and judgments and lack of compassion. I have to work against all of those things in myself, and I have to fight against the misogynist in myself. Because we all have a misogynist and we all have a white supremacist in our heads, all of us. Even (and in some cases, especially) Black people.

We’re currently being faced with a lot of hard work and we're asking a lot from ourselves and one another right now. But I do hope against hope that one day folks will recognize the value, the inherent value, of women (and of Black women in particular, because we are exceptionally targeted, undermined, and devalued in this country), and begin to treat us with the human rights, dignity, and respect that we deserve, that every single living breathing being, deserves. Folks love to run around screaming ‘all lives matter.’ Well, show it. Prove it. I’m hoping that we will get the love that we deserve, and the respect, and the protection. Because we need it. And we deserve it.

__

Too Much Midnight by Krista Franklin is available in hardback as a 2020 release by Haymarket Books (Chicago).

Krista Franklin is a Chicago-based writer and visual artist whose work has appeared in Poetry, The Offing, Black Camera, Copper Nickel, Callaloo, BOMB Magazine, Encyclopedia, Vol. F-K and L-Z, and the anthologies The End of Chiraq: A Literary Mixtape, The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop and Gathering Ground. Her chapbook of poems, Study of Love & Black Body, was published by Willow Books in 2012.

—